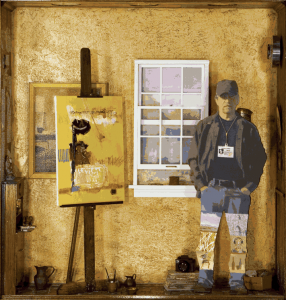

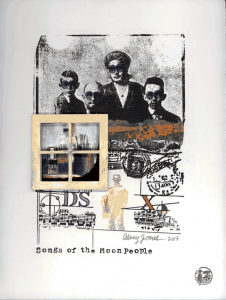

Alvey Jones: WINDOWS

1. Alvey, you have a background in painting and art history and hand-made artist books. What else do you have a background in that you feel is relevant to your art ‘problem solving?’

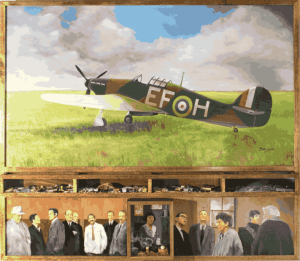

A. Ever since I can remember, I spent my time making things. When I wasn’t making things I was thinking about how to make something. This led to drawing what I had made or drawing a plan for something I wanted to make. Whenever I visited my grandfather he would give me a cherry soda and put me in the basement where he had all kinds of wood and a bench of tools and let me do whatever I wanted with them. I’ve been working in basements ever since. Then when I was in the third grade Bill Miller showed me something called a model airplane. Instantly, I fell in love with the shape of the thing, it’s complexity and structure. For the next ten years all my creative energy focused on understanding, planning and building models of ships, cars and airplanes, often from scratch and in the greatest of detail. People often complain today of how much time kids spend in front of computers. Well, I spent 12 hour days for entire summers, to the despair of my parents, building and drawing my precious models. I did play a lot of baseball, though. I think this long apprenticeship of designing, drafting and constructing these two- and three-dimensional objects lies at the core of my capacity to do the work I do today.

2. You seem equally versed in painting on the large scale and painting in a miniature scale…and everything in between. What would you say is the biggest challenge in changing scales as you produce a piece of art?

A. I’ve never had a lot of room in which to work. Basements are often cramped quarters, so I’ve had to be resourceful in organizing my work area and tailoring what I do to fit that space. I’m most comfortable working at a small or moderate scale so that usually works out. There are times, however, when I want to increase the size of what I do, just to give a different perspective to the issue I’m struggling with (but not so big that I can’t get it in my car and transport it). I find I have to concentrate more when I do that and I feel I have to work harder to keep the idea I want to communicate from slipping away from me. I seem to lose some intimacy, density and deep texture when I do that. That’s about as close as I can come to characterizing that challenge.

3. When did you first know you wanted to be an artist?

A. For a very long time I didn’t realize one could “be” an artist. I didn’t know one could have a career in Art. Making things, including artworks, was just something I did all the time. Then one day a guy walks into a bar . . . (that’s how it always begins, isn’t it?). Anyway, about the time I graduated from high school, a friend of mine met a guy in a bar who was selling correspondence courses in commercial art sponsored by Norman Rockwell and several other famous New York Illustrators and designers. My friend knew of my artistic activities because I had pinstriped his ’53 Pontiac, so he gave the guy my name. I started the course and about halfway through it it dawned on me that this was something that I might really want to do forever. I never finished the course, but it did inspire me to head to the local university, walk in the front door and ask them to sign me up in the art department (you could do that in those days). There was a professor there who taught the design classes but was also a recognized painter, what was then known as a Fine Artist. He encouraged us to look beyond the narrow field of commercial design to the rich, vast history of Art. That was when a whole new world opened for me.

4. Painting, assemblage and hand-made book-making all call on quite different sensibilities. How do you feel working in this variety of media feed into one another?

A. To me one of the most important artistic rituals, if you will, is moving from one way of working, one set of media, to another in the course of pursuing an idea. The cross-polination of forms, methods and compositions, or anything else is what I think gives my work the resonance I want in it, though everyone doesn’t see it that way. A series of collages leads to an assemblage and then that’s all incorporated into a book. A natural progression for me. Simply put, working in one medium often gives me ideas that I may apply in another and I rarely hesitate to pursue them. I’ve always felt it to be a comfortable way of working. Not that it’s always successful. As you know, I very often combine many different media in one work (all of the above), something not rare these days. But when I was starting out that was not something serious artists were expected to do. Very early on I was admonished by a professional for using two distinct media in one work. I was puzzled but I thought it a useful way of generating new approaches and continued to do so. It’s all just making and that’s the joy in it.

5. What is (are) the most satisfying thing(s) to you when you’ve finished a piece?

A. Usually it’s the freedom of going on to the next piece, having worked out what was disturbing me about current one. It’s the possibilities lurking in the next encounter with a blank canvas or that piece of junk I just found in the road.

6. Do you have a favorite, or 2 or 3, piece(s) of art made by another artist (living or dead) and why?

A. Several years ago I made an artist book (one of my more obscure) which contains reproductions of 52 of my favorite paintings. My very favorite is probably the one I used as a frontispiece. It is “The Goldfinch,” painted by a pupil of Rembrandt, the Dutch artist Carel Fabritius in 1654, now in the Mauritshuis in The Hague. Not much of his work is still around, most of it having been lost in a gunpowder explosion in Delft in 1654. As for why any of the works in my book are favorites, let me, if I may, quote from the Preface to my book:

“From these paintings and these experiences come some striking form, some arrangement of color, some personal spark, some play of light that becomes the launching pad for our fresh efforts. The meeting of mind, materials, tools and history (your own and that of the world) goes into the making of the work of art that is the creative process. To see this is to have a secure grasp of the creative process. There emerges a resonance between the artist and the past (a past partly seen through the paintings in this book) that propagates a cohesive and compelling work of art, a work of substance, permanence and solidity. In the end there also exists the simple pleasure of enjoying the paintings for their beauty, intelligence and inspiration.”

7. If you could invite 3 artists, living or dead, to your house for dinner, who would they be? JUST KIDDING, you don’t have to answer this one.

A. I can’t think of an artist I’d like to have over for dinner, particularly some of my favorites. But I have long had the fantasy of my wife, Domenica, and I having a dinner party with Woody Allen, the singer-songwriter Paul Simon and the actor and writer Wallace Shawn. Domenica, however, would not be interested. She would like to have Abe Lincoln, Leon Trotsky and Harpo Marx over for pasta.

8. Do you have a particular muse that keeps pulling the art out of you?

A. I don’t know of a particular muse. I just have to do it. As the New York artist Lionel Dobie says, “It’s not about talent. You make art because you have to. You have no choice. If you give it up, you weren’t a real artist to begin with.”